20.4.14

Today I rode my bicycle down Twentynine Palms Highway to pick up trash in Section 33, a nature preserve bordering the highway. The preserve is owned by the Mojave Desert Land Trust who organized the clean up event. I locked up my bicycle against a round, sort of trash can looking cover with an advisory message about a gas line that I didn’t stop to read and climbed up the soft shoulder into the desert. A group of teenage boys were already filling up large plastic bags with trash that had been thrown or accidentally blown out of people’s car windows, deliberately dumped, discarded by hikers, who knows. An employee of the land trust came over and introduced himself and his kindergarten-aged son, “This is Tommy, the Chief Engineer.” He handed me a black plastic bag said we are trying to pick up, “anything that is not natural”.

We spread out in rows like a disorganized military formation and combed a fifty-foot wide strip of desert tracing the highway. I wandered through the low vegetation, scavenging toilet paper wrapped around hedgehog cactus making it look like a miniature mummy, candy bar wrappers threaded between the spines and purple flowers of beavertail prickly pear, flickering silver plastic wrapping woven in the zebra striped branches of creosote bushes, rusted cans and broken beer bottles collected in the dales of washes. I lamented about the plastic bags that blew away after I left them in the drying rack in the outdoor kitchen my first day here. I looked at the teenagers and remembered what it was like to be their age and find myself at a community service event feeling half-abducted, half-fascinated at a situation totally outside of my routine. I thought about how we have being mining landfills for metals and other useful materials and wondered if we will reach a point where we begin scavenging the desert for them. The most annoying and dishartening trash were the pieces of plastic that would just break into infinitely smaller pieces as I reached down to pick them up—making me feel like I was only doing more harm in my attempt to help—a feeling I have so often in my life it trails me like a shadow.

There are varying estimates for how long it takes plastic to degrade—or if plastic degrades at all and instead just fragments into smaller and smaller pieces. Plastic water bottles are estimated at 500 – 1000 years. There is also a lot of trash that isn’t plastic that will linger longer than I will live: an aluminum can takes 80-200 years to degrade, a rubber tire 80-2,000 years, cigarette filters may break down in 10 years, but their acetate fibers do not fully degrade—nor do the 4,800 chemical compounds in cigarettes, at least 69 of which are carcinogenic and bleed into the ecosystem they are extinguished in.

When I bent down to pick up a burst balloon shriveled up like a squid, a cactus stuck me in the leg. As I pulled the cactus spine out my sock, the spine pulled my skin outwards, making a thin and tight peak. I got a little worried that it wouldn’t come out because of the barbs lining its surface, but it finally relinquished and I followed a couple up a sandy wash pulling up half-buried plastic bottles and cardboard. A woman with a broken swing wrapped around her head carrying a bag filled twice as big as mine smiled and said, “I wear my trash well”. Renée and I talked trash for a while, “It’s when I see the younger people littering that I lose hope. The older people still do it but that doesn’t bother me because they grew up in a time when you could just throw things on the ground because everything was biodegradable.” I thought about how her observation of this shift in postconsumption pertained to my recent trip to Jordan staying with a group of Bedouins in the desert and all the trash that tumbled through the wind past their goat hair tents. “I don’t feel angry at the people that litter, but the companies that design this indestructible stuff in the first place,” I tossed in as I told her about one of my friends, who is the most staunch environmental activist I know, who hates recycling because it puts the onus on the consumer. I pulled a piece of paper out of the sand and dusted it off to read it:

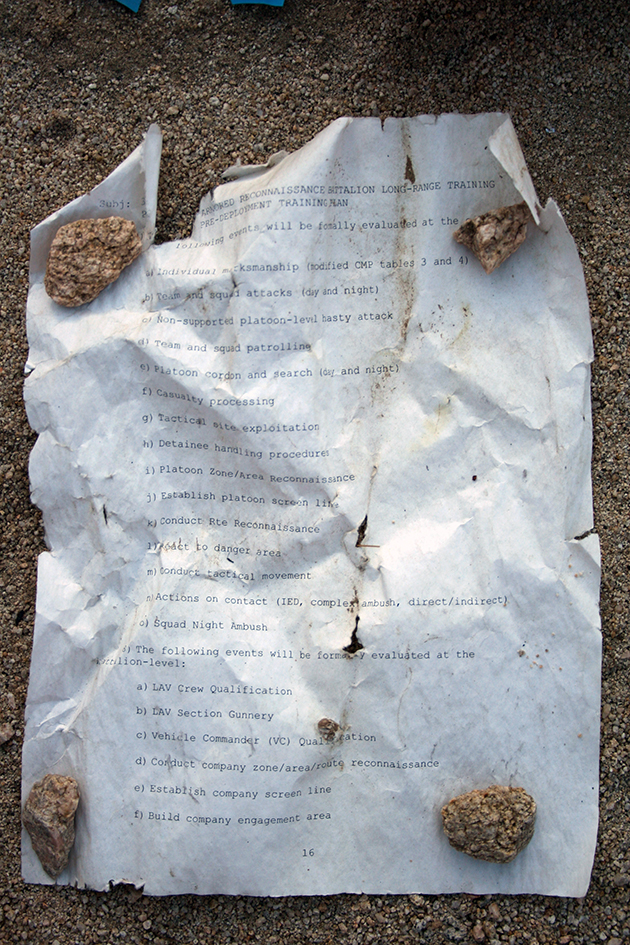

3rd LIGHT ARMORED RECONNAISANCE BATTALION LONG-RANGE TRAINING PLAN AND PRE-DEPLOYMENT TRAINING PLAN

I scanned its list of “events that would be evaluated at the company level”:

a) Individual marksmanship

b) Team and squad attacks

f) Casualty processing

g) Tactical site exploitation

h) Detainee handling procedure

n) Actions on contact (IED, complex ambush, direct/indirect)

o) Squad night ambush

p) 81mm mortar platoon live-fire

I figured it must have blown out of a marine’s car, driving to the Twentynine Palms Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, the largest Marine base in the country, located just 15 miles from Joshua Tree and measuring 295 square miles—and planning to expand. Further up the wash I teased another sheet out the thorny branches of a cat’s claw:

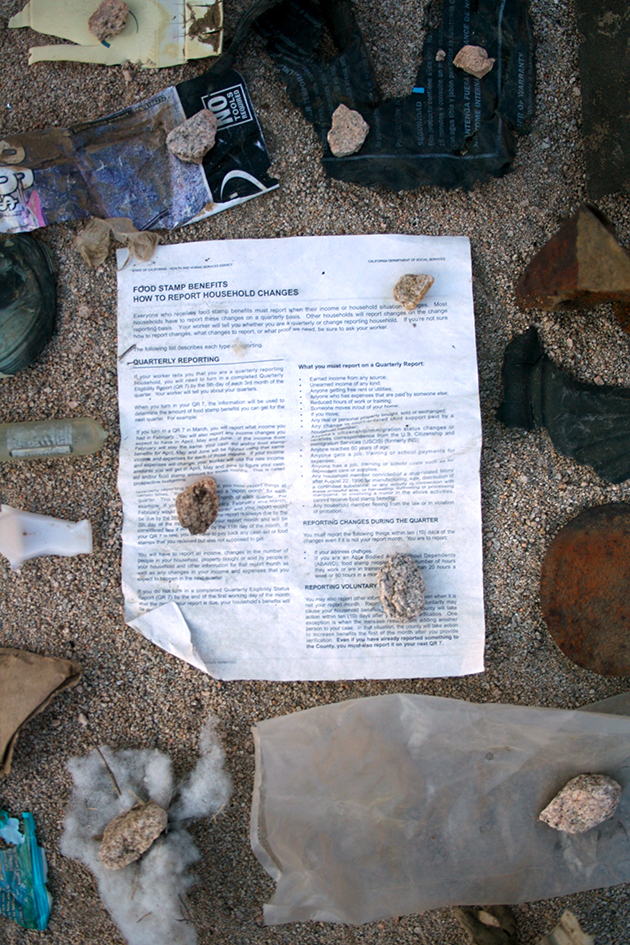

FOOD STAMP BENEFITS: HOW TO REPORT HOUSEHOLD CHANGES

The list of “What you must report on a Quarterly Report” included:

- Anyone’s citizenship/immigration status changes or receives correspondence from the US Citizenship and Immigration Services

- Any household member fleeing from the law or in violation of probation

- Any household member convicted of a drug-related felony after August 22, 1996 for manufacturing, sale, distribution of a controlled substance…or harvesting, cultivating or processing marijuana, or involving a minor in the above activities.

- Any real or personal property, bought sold or exchanged

- If you move;

- Someone moves in or out of your home

Depending on who is counting, the federal government spends 28-38% of its annual budget on the US military. It spends $708 billion on the Department of Defense while spending $80 billion on food stamps, $77 billion on unemployment compensation, $800 billion on medicare and medicaid, and $769 billion on social security. 20% of the total federal budget goes directly to the Department of Defense and 8-18% is dispersed under different departments for things like nuclear weapons, FBI, CIA, Homeland Security and NASA intelligence gathering, veterans, and interest on debt incurred from past wars. U.S. military spending accounts for almost half of the entire world’s spending on war and weaponry. The US spends more money on military than the next top 10 countries combined (China, Russia, UK, Japan, France, Saudi Arabia, India, Germany, Italy, Brazil). There are no available figures for how long it takes the US military to decompose.

Our garbage route ended at an industrial dumpster across from the High School were we pooled our collections until the dumpster was about 1/3 full and a rusted spring mattress nearly peaked out of the top. I watched as the teenagers ate Dominoes pizza and I felt like I was really back in the US after being gone in Europe and the Middle East for the last four months. As the teens began to pile onto busses, Danielle the director of the land trust explained that they were marines, so new they weren’t allowed off the base yet except for special events like these.

Katherine Ball was in residence as our HDTS Scout in Spring 2014.

The HDTS Scout Residency is dedicated to learning more about the people and places that make up our diverse and ever evolving community.

Originally from Detroit, Michigan, Katherine has worked on projects around the world, exploring alternatives to the dominant discourse. Some of these include: bicycling across the US to interview Americans working on small-scale solutions to the climate crisis, coordinating a national day of action to halt business at banks and corporations unduly influencing state laws, living in an off-grid floating island building mushroom filters to clean a polluted lake, and studying the behaviors of various species acting as the ecological counterpart to civil disobedience. An amateur in the best sense of the word, Katherine strives to give more energy to our dreams than our fears.

During her residency, Katherine engaged in a series of in-depth interviews and conversations with high desert residents, focusing on our human impact on the desert landscape. Her book represents a condensed version of those discussions, encompassing water conservation, big solar, wildlife linkages, and asks: what is a sustainable life in the desert?