Living in the Wash with Tova, Diana, Anna, Nora, Katy, Lilly and Rose

What does it mean to live in a place? Over two years of moving from place to place, wherever I arrive people always ask me where I live. That is a good question. I have been trying to expand my perception of where I live as something beyond the borders of a city. To understand wherever I am is where I am living—and to treat that place with the respect one traditionally treats their “home”. Is home a structure or an essence?

Similarly, I have been trying to treat the people that care for the place I am in with the respect I would treat “my community” if I was living in one place—why should how I treat people be based on how long I will be in the same immediate space as them?

There is a lot of talk about NIMBY issues: Not In My Back Yard. I am trying to grow into the idea that our backyards extend beyond the borders of our fences. As Aldo Leopold wrote, “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

When I’ve lived in different cities in Europe, I used to feel bad when I didn’t know the language, but as I started to become more aware of refugee and immigrant populations living in these cities and how language is often seen as a barrier to be overcome in the process of “integration” and “assimilation”, I began to wonder if there are moments when localism slips into forms of nationalism or fascism.

I should be clear that I have a great deal of respect for people who live in a place long term, caring for the land and forming deep bonds with the people around them. At the same time, I have noticed in Joshua Tree that there are many temporary communities that pass through here: hikers, climbers, tourists, musicians and the many people who commute between here and LA for work and life. This spectrum of temporary communities is a real factor, one that often unaddressed in discussions around localism.

I spent the last ten days living with seven women in the wash at A-Z West. We arrived here from Sweden, LA, Portland, Denver, Greece and Massachusetts. Our living together might have been short in time, but it was deep in experience. By day, we would cook in the outdoor kitchen, hike in the canyons, and explore the larger Joshua Tree area attending events like the farmer’s market, the swap meet, concerts at Pappy and Harriet’s, sound baths at the Integatron, and the karaoke at the saloon. At night, we would descend into the Wagon Stations, some of us sleeping with the hatch open and gazing out at the stars. We also lived our daily lives here: bicycling along the highway, washing our clothes at the laundry mat, shopping at the grocery store, filling up our tanks and buying ice at the gas station in town. We also breathed in the bacteria, fungi, and dust in the air and exhaled some of our own. We were not locals, but we were living here: sharing moments of kindness, appreciation, intimacy, wonder, and friendship. I asked all of these friends to contribute a few words about why they were drawn to Joshua Tree, what it has meant to them to share this place, and how what they experienced here extends into their lives beyond Joshua Tree:

“In the high desert there is a heightened awareness of isolation and compelling freedom. People migrate from the city to stretch out among the skeletons of former homesteads that are discernible across the landscape. The expansiveness surrounds you allowing uninhibited thought while everyday survival and simple creature comforts cultivate reconciliation.The native plants hold fast as an unintended testament to primitive resilience.” – Nora Rolf

“My music has always been based in the desert—I recorded an album called Mountain Rock in a Quonset hut outside of Tucson many years ago. Most recently I released an album called California Lite, on which I examine image vs. reality in southern California, simulation, and our obsession with transportation and technology. When I have visited Joshua Tree in the past, I have always enjoyed the unbelievable natural setting which is so epic and beautiful, but also taken simultaneous notice of the dizzying barrage of commercial aircraft that constantly, almost mockingly, zoom overhead. Joshua Tree’s relative proximity to urban centers such as Palm Springs and Los Angeles ensure that this desert paradise is always below the flight path. The pervasive human element in this “God-like” place creates a fascinating friction. I approached A-Z West because I know that working in this setting will imbue my work with that same friction.” – Katy Davidson

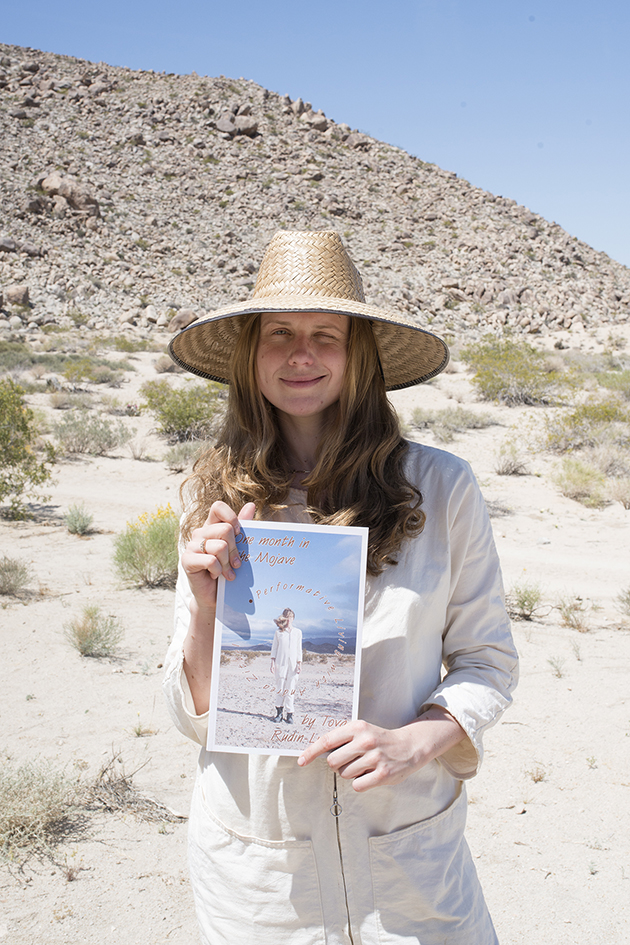

“I was here about two and a half years ago when Andrea was just starting to build up the wash as it is now. Before the luxurious showers, kitchen and highly functional shitters were installed. I was kind of a guinea pig, first person to stay in a Wagon Station for a whole month. Back then I shared my experiences on a blog which I later turned into a book – One month in the Mojave. Bringing the book back ”home” was a great reason to finally make it back here. This time around I´ve been able to do things I thought I would do, the last time I was here. I´ve read books. I´ve meditated on a rock and I´ve had time to almost get a little bored. It´s good to be back.” – Tova Rudin

“I live in Los Angeles, which is technically a desert, although everyone likes to forget it. I came to A-Z West to refresh my memory, and to reset my thinking, to start from scratch upon my return to the city.” – Anna Reutinger

“It is clear why I came back to the desert and the A-Z West encampment a second time. When I am not living outdoors, in the desert, the wonder that I get from it slips away, drowned by the stimulation and chatter of the concrete city. I am so happy to have experienced a different way to live, that connects me to my participation in and with the living earth. I hope I keep coming back to Joshua Tree and this mindset.” – Lilly Fein

“Like so many others of my generation, at 19, young and carefree in halter tops and Indian skirts, we, that is my best friend and I, ventured out west and back, with our thumbs out; fearless, young and invincible. It was how it was done. An experience that I would never take back, however one I am grateful my daughter in her search, did not feel the need to pursue.

However, at 21, my daughter Lily, asked me to return with her on her second visit to A-Z West, where she had an experienced something close to her heart. It had been 40 years since my little adventure out west so I couldn’t imagine not making it happen. At 59, I had few expectations. I only knew that I would perhaps get to know my daughter better and have more opportunities to be more in the moment with her, more than our everyday lives back east would allow. So I jumped at the opportunity and suggested we make it a 5 week mother/daughter trip, and include many of the places that touched my life when I was her age on my adventure. So we are doing just that and more.

The experience thus far, has mostly been at A-Z, an experience I can add onto my list of life experiences that I would never want to take back. Luck plays a big role in experiences like these, and ours was luck to have. We were with an incredibly diverse, curious, intelligent, interesting and talented group of people that made for a genuinely caring and thoughtful community. I identified with everyone, as I felt like it was like yesterday that I was in their place. But more than ever, I was reminded of who I was when I was young, when the transition of my dreams transformed into a new reality, and the challenges I faced made me who I am today. I was reminded of how time and experiences help one shift into acceptance, and how the will to teach your children to make some of those dreams happen, become a reality.” – Rose Srebro

Katherine Ball was in residence as our HDTS Scout in Spring 2014.

The HDTS Scout Residency is dedicated to learning more about the people and places that make up our diverse and ever evolving community.

Originally from Detroit, Michigan, Katherine has worked on projects around the world, exploring alternatives to the dominant discourse. Some of these include: bicycling across the US to interview Americans working on small-scale solutions to the climate crisis, coordinating a national day of action to halt business at banks and corporations unduly influencing state laws, living in an off-grid floating island building mushroom filters to clean a polluted lake, and studying the behaviors of various species acting as the ecological counterpart to civil disobedience. An amateur in the best sense of the word, Katherine strives to give more energy to our dreams than our fears.

During her residency, Katherine engaged in a series of in-depth interviews and conversations with high desert residents, focusing on our human impact on the desert landscape. Her book represents a condensed version of those discussions, encompassing water conservation, big solar, wildlife linkages, and asks: what is a sustainable life in the desert?