Reality is Like a Horserace

I first met artist and craftsman Desert Mike when I thought I might move into a house on his compound. I was greeted with a space full of rusty objects and a gentle man with a love of small and beautiful found things, with kind eyes and wiry glasses. Today I visited his home on Windsong Avenue to hear his story. He offered me wine or tea, coffee or water, and was excited to show me around his house, which was unusally dark, with maroon curtains blocking the desert bright, and jars of dried goods. HIs modern, southwest inspired furniture pieces decorated the walls and corners, and folded objects with stories emerged from some of them, like a French flag from WWII given to an American soldier by his French lover…

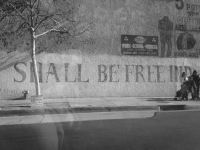

He shows me the tiles of millionaires houses, which he found by the side of the road, that now make up his bathroom walls. “Free, it was all free,” says Desert Mike. “They don’t want you to know it, but you can get a lot for free in this world! I am going to write some kind of piece on dumpster diving…” I too have been collecting objects found in the desert, tin cans with flowering bullet holes, fragments of turquoise china, covers of books…the desert ages real functional things in a way that renders them almost mystical, formless, separate from their original use value in the known world. Mike’s space feels clean and neat, and taxonimized in a way that is familiar from trips to the back room of the Natural History Museum. Every object has a reason for being where it is and exists within a grander classification system, imperceptible when viewing a small group of objects on their own.

Desert Mike works on his assemblage works slowly; each and every tiny piece that he touches has a specfic place where it is supposed to go. He tells me that things don’t always fit together the way he thinks they will; in his head a pea-sized turquoise pyramid might fit nicely into an old gear of a watch, but when he does it, something doesn’t feel right. So he spends a lot of time sitting with a specific placement of components, looking and feeling and moving things around. He is particularly excited about 4 new pairs of surgeons forceps he recently purchased in Quartzite, for only 10 dollars (!). He thinks they are worth at least $25 a piece!

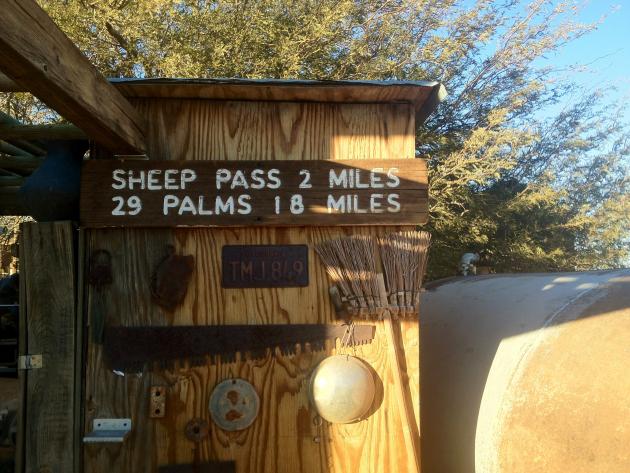

Mike first came to the desert with his family in 1956 to a small homesteaders cabin in 29 Palms that his father bought for “dirt cheap.” Back then there was NOTHING here, he says, it truly was the wild west. The family’s cabin was on Dump Road, and the first cast off objects that young Mike was drawn to were a bunch of wooden national monument signs, with the words carved out with a router in a beautiful old fashioned typeface. He saved the lot of them and one still hangs on the building next to his house. His family continued to go out to the cabin for all of his young life, and Mike felt drawn to the openness and outsider feel of the desert land.

We speak about the mystical and the mythical, the interface between the humble and the divine, and Mikes understanding of some greater, other-dimensional being that designed all of the parts of this world. There are other beings vibrating at distinct frequencies that we cannot see or hear, on planes close to but separate from the reality we experience, and we all have the right to our beliefs about the world. “Reality is like a horserace,” he says, “everyone is betting on their horse.” He brings out a piece built on a discarded motherboard, that feels like an extension of our conversation about reality. Glued onto the circuits and silicon are objects from nature; a fossilized snail shell, a fragment of peridot, a circle of turquoise. I remark that it is difficult to tell which parts were added, and he smiles, “good.”

Mike went to school for furniture making, and started a woodworkers cooperative in Long Beach in the early 80s. He made fine furniture, with smooth, varnished wood for years for a living, and when he moved out here in 1987, he craved a return to natural unfinished wood, and the textures of different types of trees. Now he carves his pieces with enhanced textures, taking wood grain to a new dimension. Some of his furniture has crystals embedded in in, which lights up with the technology of LED lights! “I think I am a moth,” he said as he explained to me that he had always been attracted to light.

This is a Ritual Cabinet, a cabinet for individuals rituals, like “taking vitamins or burning insence.”

Katie Bachler was our first HDTS Scout, and was in residence from 2012-2013.

The HDTS Scout Residency is dedicated to learning more about the people and places that make up our diverse and ever evolving community.

During Katie’s residency, visitors were invited to drop into the HDTS HQ, the Scout’s home base, to meet Katie, who could be found making maps, hosting conversations, and baking bread – in between her off-site adventures around town and out in the field.

Katie had a lot in store during her time here, including:

- a series of talks featuring local experts

- joining together to create a web of knowledge

- a research library and archive documenting the many spaces, places, plants, and people that make up this special region

- casual conversations with drop in visitors over tea

- site visits and field trips around town

Katie engaged the community by instigating map-making and rag-rug braiding workshops, the Scout’s Book Club, Art in the Environment classes for desert kids, casual conversations, site visits and field trips—all shared in her Scout’s blog, which serves as the foundation for her book.