Give and Take: Iraq War Memorial Tattoo Project

Give and Take: Some war tokens

When you drive up Adobe Road towards the Twentynine Palms Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, the largest Marine base in the country, the road is flanked not by the namesake palms or the decommissioned planes and guns that welcome you at other bases. The sole objects of monumental scale are the town’s “Oasis of Murals,” illustrating local prospecting history, or desert flora and fauna, serving as much as distractions from the yawning adjacent vacant lots as edifying visual narratives. The most ambitious mural, Don Gray’s “Operation Iraqi Freedom” is surprising in its focus on battle confusion, or Marines rescuing their wounded. Saying “I had to talk myself into this one” because he didn’t want to celebrate war, the mural can’t be seen until you’re heading out of town, or leaving base, depending on whether you’re a tourist or a soldier. Aside from Gray’s haze-filled depiction of brotherly loyalty amidst battlefield confusion, the lion’s share of memorializing takes place nearby in more prosaic places, and on a far more intimate scale.

Brightly lit with florescent lights and smelling of disinfectant, the six or so tattoo studios of Adobe Road exude the antiseptic feeling of the clinic as much as being sirens of what Adolf Loos famously called the crime of ornament. The days when the tattoo parlor attracted only bikers, soldiers and denizens of the underworld have been traded for a professionalization marked by blood-borne pathogen certifications, sterilizers, reams of carefully laid out plastic and examination gloves. So when the Marines go in to get their tattoos (one thing hasn’t changed) the feeling is as much akin to a medical procedure as a ritual wound/image.

As an observer, this scene is filled with a canny likeness to those I experienced 18 years ago as a young DWNAD (Dependent Wife, Navy Active Duty, the icky-sounding acronym pronounced “Dwah-Nad”), a child bride, as my friends called me, married to my long-time neighbor who became a Navy flight surgeon. Attached to a squadrom of Marine helicopter pilots, and periodically sent to 29 Palms for combat training, my then-husband indulged my curiosity about the clinical setting my letting me pose as a medical student so I could, up close, observe him cleaning out wounds, express particularly nasty abscesses, or later, when we became a urologist, cut open testicles and the like. And so I’ve come back to Twentynine Palms; it’s another Bush, another desert war, again a Marine in the chair under the knife or needle, but this time it’s me who’s probing the wounds.

Drawing attention to the fact that Marines get tattoos, even in great numbers, is like reminding us that the sun comes up every day, or that cops are corrupt. But their practice of getting memorial tattoos, sometimes even before heading off to war, is both curious and haunting. At once intimate and monumental on a bodily scale, the tattoos seemed to function as a prompt for both stories and silence. Some buddies design a tattoo together, agreeing to get the tat if one of them dies. Others simply get one, in advance, knowing that one of them will “fall” as they call it. Often, a group will get matching tattoos when they return with a common symbol, or with lists of their dead buddies’ names. More often than not, the design involves some version of the “soldier’s battle cross,” a half-cross, half-skeleton arrangement of a soldier’s helmet atop his rifle, jammed near his empty boots with dog tags hanging down.

The site of my project is not only the bodies of Marines and the images that they create in relation to the war. It’s located in the conversations with the tattooists, waitresses, shopkeepers and residents of the Twentynine Palms and Joshua Tree area. It exists in the stories and shared burden of witnessing what happens to the 20 year olds who act as the pointy end of our nation’s foreign policy stick. Extending this sense of exchange, I’ve created a token for you to take with you, and a chance to leave something of your own behind.

—Mary Beth Heffernan (from the HDTS 5 catalogue)

Photos:

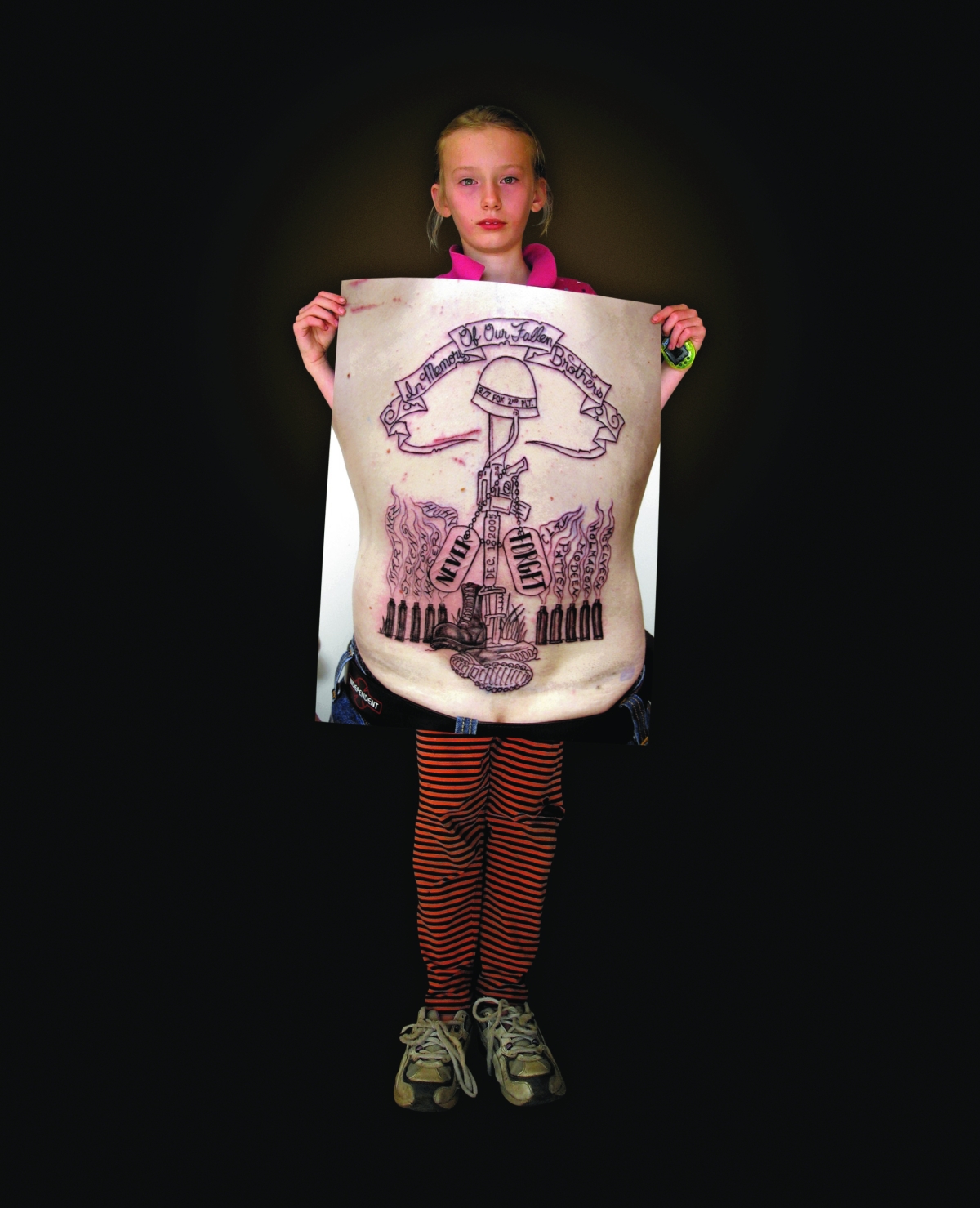

Girl with poster, Mary Beth Heffernan, 2006.

This girl attended HDTS 5 with her mother and twin brother. When she picked up the poster, she draped it around her back and said, “Mommy, I want a tattoo!”

Young Marine being tattooed with the names of the 10 of 2/7 Fox Company Marines who died in a December 1, 2005 blast, Mary Beth Heffernan

¸.·ℳ¸.·´¨)𐌄 ¸.·*¨ɱ)

(¸*.ᴑ·´ (¸.ʀ·´ .·´🄨 ¸

MAY 6, 2006 - MAY 7, 2006